Secondary Meaning in U.S. Trademark Law

Trademark law does not merely protect words. It protects the psychological relationship between a word and a source. Secondary meaning is the doctrinal mechanism through which that relationship is legally recognized.

At its core, the doctrine reflects a simple commercial truth: a term that once described a product can, through use, promotion, and public exposure, come to identify a single producer. When that shift occurs in the minds of consumers, language is transformed into property.

For lawyers working at the intersection of intellectual property, media, and entertainment, secondary meaning is not an abstract evidentiary exercise. It is the point at which branding becomes a legally enforceable asset and where marketing strategy turns into litigation leverage.

The Statutory Foundation and Conceptual Framework

The Lanham Act does not treat all marks equally at the moment of adoption. Distinctiveness determines both registrability and scope of protection.

Section 2(f) recognizes that a mark which has become distinctive of the applicant’s goods in commerce may be registered even if it is not inherently distinctive. This provision reflects marketplace reality rather than creating an exception to the rule.

Secondary meaning exists when the primary significance of a term in the minds of the consuming public is not the product itself, but the producer.

The legal inquiry is therefore not linguistic. It is empirical and perceptual.

Courts are not asking what the term means. They are asking what the public believes.

The Spectrum of Distinctiveness Revisited

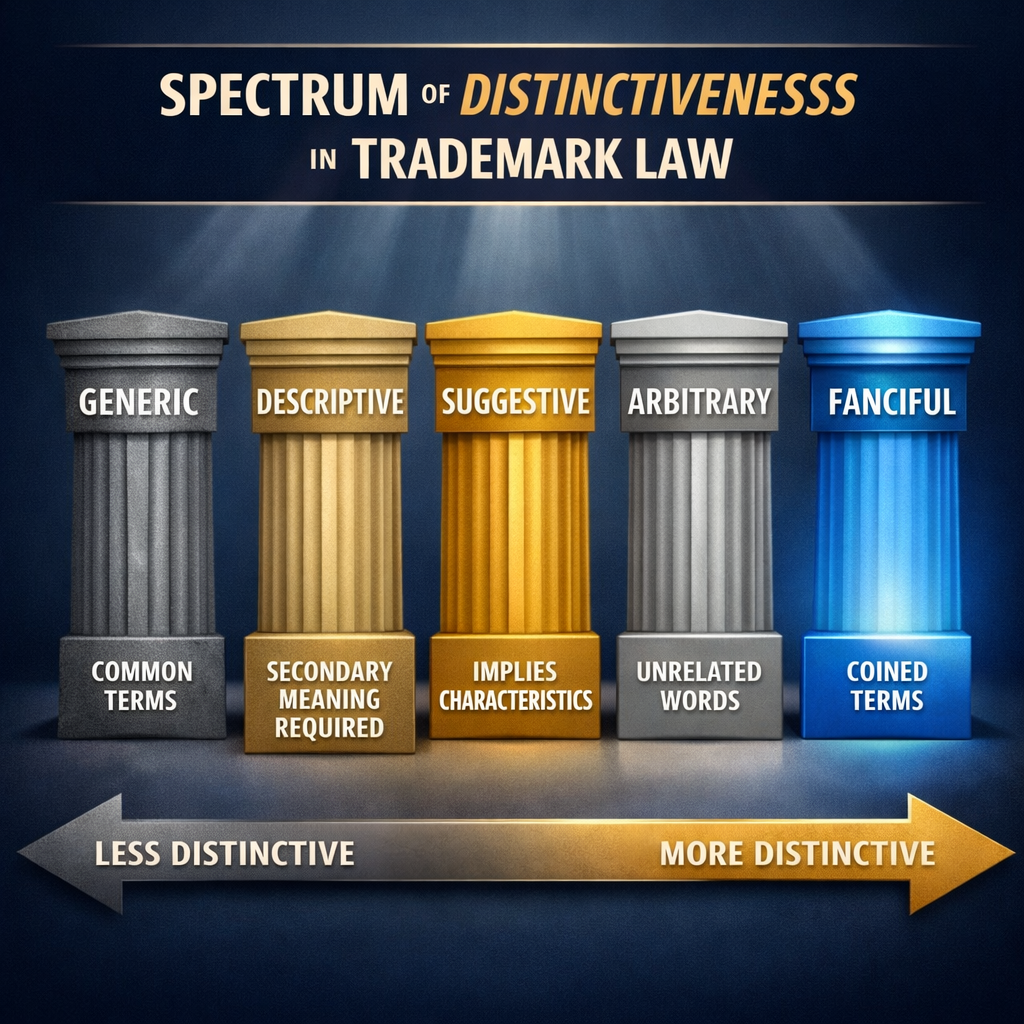

Secondary meaning operates only within a defined doctrinal space along the spectrum of distinctiveness. Generic terms are excluded from that space entirely because they constitute the basic vocabulary of the marketplace. They name the product itself rather than its source, and for that reason they can never be appropriated by a single producer, regardless of the scale of use or the amount of promotion. Granting exclusive rights in such language would deprive competitors of the words necessary to describe their own goods and services.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are suggestive, arbitrary, and fanciful marks. These designations are considered inherently distinctive because, from the moment they are adopted, they function as indicators of origin rather than as descriptions. They do not require proof of acquired distinctiveness; their legal strength is immediate, and their registrability does not depend on the development of consumer association over time.

Descriptive marks occupy the middle ground between these two poles. They are commercially appealing precisely because they communicate information quickly and efficiently to the audience. A descriptive title can signal genre, format, or subject matter in a single phrase, which is why such names are so common in media and entertainment. Yet that same communicative quality makes them legally fragile, because the law must preserve the ability of competitors to use similar language in good faith. The designation begins its life as part of the shared linguistic resources of the industry rather than as a proprietary sign.

Secondary meaning functions as the bridge across this divide. Through sustained and recognizable use, a descriptive term can move from being understood as informational to being understood as identificatory. The words themselves do not change; what changes is the perception of the audience. When the public comes to associate the term with a single creative or commercial source, the designation leaves the realm of common vocabulary and enters the realm of protected identity.

This progression is particularly visible in the entertainment industry, where film titles, production-company names, digital platforms, and recurring content brands often start as straightforward descriptions. Over time, through distribution, publicity, critical attention, and audience loyalty, those same designations can acquire a meaning that points not to a type of content but to a specific origin. At that moment, a term that once belonged to everyone becomes capable of belonging, in a legal sense, to one.

The Role of Trademark Counsel: Proving Secondary Meaning in Registration Practice

For trademark attorneys, a claim of acquired distinctiveness under §2(f) is not a routine filing. It is one of the most complex forms of registration practice.

Most secondary-meaning cases arise after a descriptiveness refusal. At that point the application ceases to be a standard prosecution matter and becomes an evidentiary proceeding.

Counsel is no longer simply responding to an Office Action. Counsel is building a factual record designed to prove consumer perception.

The work begins with a threshold legal determination: whether the mark is capable of acquiring distinctiveness and whether the client’s use has reached that stage. A premature §2(f) claim can permanently weaken the application and create admissions that will later be used in enforcement or litigation.

Once the strategic decision is made, representation shifts into evidence architecture.

The attorney must assemble proof demonstrating the transformation of the term from description to source identifier. Duration of use is evaluated not in isolation but in relation to market exposure. Advertising is analyzed for its brand-conditioning effect rather than its budget. Sales success is examined as evidence of public recognition. Media coverage, industry references, licensing structures, and digital presence all become part of the evidentiary narrative.

In substantial matters, survey evidence must be coordinated with expert methodology that will withstand both USPTO scrutiny and later judicial review.

This is not mechanical submission of documents. It is the construction of a legally coherent story supported by admissible proof.

A properly developed §2(f) record performs multiple functions simultaneously. It is a response to the examining attorney, a future enforcement tool, a valuation document for the brand, and the foundation for federal litigation.

For entertainment and media clients, the complexity increases further. Recognition may exist within a defined audience segment, within a distribution channel, or on a specific platform. Counsel must define the relevant consuming public with precision and prove distinctiveness within that market.

In this sense, secondary meaning is where trademark prosecution becomes intellectual-property strategy.

The Evidentiary Structure: How Courts Measure Consumer Perception

The inquiry into secondary meaning is one of the most fact-intensive analyses in trademark litigation.

Length and continuity of use create the opportunity for consumer association, but time alone does not create distinctiveness.

Advertising expenditures matter only to the extent that they demonstrate an effort to educate the public to perceive the term as a brand.

Sales success reflects the scale of exposure.

Unsolicited media coverage is particularly persuasive because it shows recognition that is not controlled by the trademark owner.

Intentional copying by competitors suggests that the mark has source-identifying value.

Consumer surveys remain the most direct and powerful form of proof.

In the digital economy, courts increasingly consider search-engine dominance, social-media engagement, streaming metrics, and platform analytics as modern indicators of public recognition.

Landmark Cases and Doctrinal Development

In Zatarains, Inc. v. Oak Grove Smokehouse, Inc., the court held that “Fish-Fri” was descriptive but protectable upon proof of acquired distinctiveness. The decision demonstrates that even highly descriptive language can become enforceable when the marketplace has been educated to treat it as a brand.

In Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Brothers, Inc., the Supreme Court held that product design can never be inherently distinctive. Secondary meaning is always required. This reasoning has profound implications for visual identity and trade dress in the entertainment industry.

In In re Steelbuilding.com, the Federal Circuit confirmed that a domain name composed of descriptive terms may achieve protectable status through acquired distinctiveness, a principle that is central to modern digital media brands.

Secondary Meaning in the Entertainment and Media Industry

Few industries rely as heavily on descriptive language as entertainment, because the title of a work is expected to communicate tone, genre, subject matter, or format immediately. A film title often signals the storyline or central theme, a production company name frequently tells the market exactly what it does, and a streaming or digital platform tends to emphasize the type of content it delivers. From a marketing perspective this clarity is commercially efficient: it reduces the distance between the project and its audience and makes the work easier to position in a crowded marketplace. From a trademark perspective, however, that same clarity places the designation on the weaker end of the distinctiveness spectrum.

Commercial logic therefore pulls in one direction while legal protection requires movement in another. The more a name describes, the more it must rely on public recognition to acquire exclusivity. When a media property achieves widespread exposure through distribution, press coverage, awards, platform visibility, and sustained audience engagement, its title or brand may cross that line and begin to function as a source identifier rather than as a description of content. At that point the name no longer refers merely to a type of film, a category of programming, or a general production activity. It points to a specific creative and commercial origin.

This shift has immediate structural consequences for entertainment transactions. Chain-of-title opinions must evaluate whether the designation has matured into protectable trademark rights. Distribution agreements and financing documents rely on the stability of that brand identity. Franchise planning, sequel and spin-off development, merchandising programs, and cross-platform exploitation all depend on the existence of enforceable exclusivity. Even the valuation of a film or television library increasingly reflects the strength of the underlying marks that anchor audience recognition across multiple projects.

Secondary meaning is therefore not simply a doctrinal concept. It is the legal mechanism that converts cultural visibility into a transferable, licensable, and financeable asset. It transforms audience recognition into a form of intellectual property that can be owned, controlled, and monetized over time.

Litigation Strategy and Burden of Proof

In federal court, secondary meaning is often the central issue.

The plaintiff must prove recognition within the relevant consuming public. The defendant attempts to show that the term still functions primarily as description.

Survey design becomes decisive. Discovery expands into marketing strategy, internal communications, licensing practices, and analytics.

In high-value entertainment disputes, secondary-meaning litigation often resembles a valuation proceeding as much as a traditional infringement action.

The Temporal Dimension: Accelerated Distinctiveness in the Digital Era

Modern media has compressed the timeline on which secondary meaning can develop. Where traditional brand recognition once required many years of continuous use in geographically limited markets, contemporary distribution models allow a designation to reach a global audience almost immediately. A streaming property can generate worldwide visibility within a single release cycle, and a digital platform can achieve dominant search-engine presence and sustained user engagement in a matter of months. Social media repetition, algorithmic promotion, binge-viewing culture, and instantaneous press circulation create levels of exposure that previously took decades to accumulate.

The doctrinal standard, however, has not changed. The legal question is still whether the relevant consuming public understands the designation as identifying a single source. What has changed is the speed and the form in which the supporting evidence emerges. Instead of relying primarily on long-term sales figures and traditional advertising histories, parties now present data reflecting subscriber growth, viewing metrics, trending rankings, verified follower counts, search analytics, and platform-based audience interaction. Recognition can be measured in real time and across multiple jurisdictions simultaneously.

As a result, the evidentiary record in secondary-meaning cases develops far more quickly, even though the underlying legal test remains constant. The law continues to require proof of consumer association, but modern media environments produce that proof on an accelerated scale and in quantifiable forms that did not exist in earlier periods of trademark development.

Geographic Scope and Bi-Coastal Practice

Secondary meaning must exist in the relevant market.

In the Second Circuit, courts often focus on consumer sophistication and commercial context.

In the Ninth Circuit, market penetration and regional recognition frequently play a larger role.

For nationally distributed entertainment properties, the question becomes whether recognition is localized, industry-specific, or widespread among the general public.

Business Strategy: Building Secondary Meaning Before Litigation

The strongest secondary-meaning cases are built long before any dispute arises.

Consistent visual identity, controlled licensing, coordinated publicity, and clear ownership structures are not merely marketing tools. They are future evidence.

A descriptive name can become a valuable asset if its use is structured with legal foresight. Without that structure, commercial success may remain legally unenforceable.

Conclusion

Secondary meaning is the moment when commercial use turns into legal recognition. A term that once merely described a product or service begins to function in the minds of consumers as an indicator of a single source. The language does not change; public perception does. What was informational becomes identificatory.

In the entertainment industry, where the name of a project is inseparable from its market value, this shift often determines whether a successful title remains just a successful work or becomes a protectable long-term asset capable of supporting licensing, distribution, and franchise development. The analysis therefore does not turn on how many years the mark has been used or how much money has been spent on promotion. Those facts matter only to the extent that they shape consumer perception.

The decisive question is simple and empirical: when the audience encounters the term, do they see a description, or do they see a source? Trademark rights arise only in the latter case, because it is that public association — not the effort behind it — that forms the legal foundation of acquired distinctiveness.

✍️ Written by Ernest Goodman, Entertainment & IP Law.

⚠️ Disclaimer by Ernest Goodman, Esq.

This article is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reading or relying on this content does not establish an attorney-client relationship. Because laws differ by jurisdiction and continue to evolve, readers are encouraged to consult a qualified attorney licensed in the relevant jurisdiction for advice tailored to specific circumstances.

.